Buy Magic Mushrooms Online In UK.

Buy Magic Mushrooms Online In Irelend

Looking For Where To Buy Magic Mushrooms aIn UK?

Where To Find Magic Mushrooms In The UK?

Get 100% Free Delivery For All Orders Of £95+

Who We Aree

We are UK’s best known mushroom growers. With more than 7 years if experience amongst our team of growers. We will always offer the highest quality products to all psychonauts in the UK. We also offer customer support with every order. All emails will be answered back within 24 hours. We are a leader in the psychedelic mushroom industry and take pride in the quality of our products and services. All our products are carefully and thoroughly tested to ensure we exceed industry standards. Buy the best quality shrooms online and get them shipped to anywhere of your choosing within the UK. Here at Buy Magic Shrooms Online UK, we bring to you a variety of high grade, naturally-grown psilocybin mushrooms from natural organic grains. With great tips from us, you are also at the right place to take a perfect trip from microdosing our dried magic mushrooms. Don’t waste anymore time and take advantage of one of our generous deals. Are you looking for where to buy shrooms online in UK? You are at the right place.

Latest Products

Same Day Delivery

For Purchases Made With Cryptocurrency

Buy Magic Shrooms Online UK

Do reach out on the live chat with your choice of strain after making payment with Bitcoin or any of the other listed cryptocurrencies on the “Checkout” page

Latest Products

Always Fresh

Quality products is what we offer. Never will you be disappointed with our products.

Secure Payment

Order using our secure payment gateway. Stay anonymous with your purchases.

Safety Precautions

Feel safe placing your order online with us. You privacy is our priority.

Quick Delivery

Quick and reliable delivery plus 100% free delivery for all orders of £95+

Best Offers

Get 5 Grams extra for all purchase with Bitcoin or other cryptocurrency listed on the checkout page.

24/7 Customer Support

Enjoy our 24/7 Customer Support system. Your satisfaction is our sole concern.

Magic mushrooms, also known as shrooms, belong to a group of polyphyletic fungi that humans use for its medicinal properties. When used correctly, magic mushrooms can help people deal with a range of physical and psychological conditions. The main ingredient in magic mushrooms is known as psilocybin. It is this compound that is responsible for the psychedelic effects normally associated with shrooms. Psilocybin, is the main hallucinogenic component found in Magic Mushrooms. This psychoactive component makes magic mushrooms the most popular naturally-occurring psychedelics. Buy Psychedelic Magic Mushrooms online in UK.

Magic Mushrooms For Sale UK

Magic Mushrooms also known as hallucinogenic mushrooms, contain psilocybin chemical which is converted to psilocin when ingested. There are different types of mushrooms. However, our focus is on the psychoactive type of mushrooms which is the most popularly known psychedelic. Are you searching for magic mushrooms for sale in the UK? Well, you can buy psychedelic mushrooms online in UK at the best affordable prices. Also, magic mushrooms are used for its psychedelic and euphoric effects to produce a “trip.” These mushrooms are called psychedelics mushroom for its hallucinogenic effects due to its action on the central nervous system. You can now order magic mushrooms for sale in UK by visiting our shop. Psychedelic mushrooms for sale UK

Many have been wondering on how or where they can buy magic mushrooms online in UK. A lot of questions from users as to where is the best place to buy dried magic mushroom in UK. Well, you are at the best place to buy magic shrooms online in UK. Here at Buy Magic Shrooms Online Store UK, we provide our clients with full guides on how to spot the best grade mushrooms. Also, we do make sure our clients have a standard dosage guide, so as not to abuse the use of psychedelic mushrooms. Further, we offer the best platform for UK users to buy psychedelic mushrooms online.

Why not visit our “Shop” and place your order today? “Buy Magic Shrooms Online” sells Magic Mushrooms, Microdose Capsules, Microdose Gummies, Microdose Chocolates, and other products related to magic mushrooms. We offer a variety of magic mushroom products at the lowest prices on the internet, with free shipping on orders over £95+! If you’re looking for mushrooms or fungi that produce psychoactive effects, we have what you need—and it doesn’t matter if you’re ordering within UK or from Germany, Austria or Ireland! Whether it’s your first time buying shrooms online in UK or not, our website has everything you’ll need to get started – including detailed information about each product.

Best Store To Buy Psychedelic Mushrooms UK

Ordering shrooms online in UK is a convenient way to get your hands on the goods. Ordering from https://www.buymagicshroomsonline.co.uk means that your package will be delivered right to your door with little hassle and no risk. You may not know how it feels until you try. Our customers say they feel satisfied knowing their order is safe and secure when they buy shrooms online in UK at https://www.buymagicshroomsonline.co.uk! What are you waiting for? Start shopping now. Take a trip with us! Buy Psychedelic mushrooms online now in UK. You can always get the best guide on microdosing mushrooms from us!

Buy Microdose Mushrooms Online In UK

Microdosing has been gaining in popularity in last couple of years as more people have begun to recognize the benefits of psilocybin in their day to day lives. Whether it be for self-improvement or relief from particular issues in their life, a microdose mushrooms has great benefits in opening the mind and enhancing relaxation. Here at Buy Magic Shrooms Online UK we are offering a way to gain the benefits without all the hassle of making it yourself. We only use capsules that are made from a natural plant based material that is Gluten-free and 100% vegan.

Each microdose capsule is mixed and measured carefully as consistency is very important when taking magic mushrooms at sub-perceptible amounts. We understand buying microdoses online can be difficult and we want you to know that we are here to make things easier. If you have any questions about our microdoses or any of our products, Please feel free to contact us at any time.

Have you been wondering what it is to microdose mushroom? Here is a brief info of what to grasp when you hear someone talking about microdosing mushrooms. “Microdosing” means taking a psychoactive substance in smaller doses in order to achieve more subtle effects. For example, a microdose of psilocybin (the “magic” component in magic mushrooms) does not cause delusions or hallucinations. The dose doesn’t interfere with the user’s normal daily activities. Recently, microdosing is becoming more popular as a medicinal drug (though usually self-prescribed).

Users usually microdose regularly only for a few weeks until their treatment objectives are met. That’s right! So if you looking to buy microdose mushrooms in the UK, we are the right place for you to check in. Also, besides the psilocybin mushrooms, there are other commonly microdosed substances like LSD, Cannabis, and various cannabis products such as pure THC. Some of these products you can also find in our shop. Here at Buy Magic Shrooms Online UK, we are all about getting our clients meet their need when it comes to microdosing. Buy microdose mushrooms online in UK from us and get a safe and secured home delivery.

Yes! It is safer to order magic myshrooms online in the UK from a safe and reliable store in the UK other than us. Our products are of the highest quality from organic natural grains. Also, all orders placed on our website are stealth packed in discreet sealed packages and registered as discreet package. Once shipped, a tracking number is provided to the client so it can be tracked all the way to your home. Authorities can’t interfere with your mail, due to special measures put in place along with the Post Office Corporation Acts which stops them from seizing the mail. So far, no one has been arrested or had any problems buying shrooms from us. Psychedelic mushrooms for sale online UK

How To Grow Magic Mushrooms

Despite the fact that magic musrhooms is considered a Class A drug, an individual can obtain a license to grow it for Home Office purposes. for every species, there are explicit strategies to be considered when growing. The hallucinogenic mushrooms which are developed the most are Psilocybe cubensis, likewise the “Mexican”. The motivation behind why they are that known is that they’re very simple to grow under controlled conditions.

For instance, in Europe, they must be inside. Again, there are different species that can develop effectively outside. Psilocybe cyanescens are local parasites that are developing on wood chips similar to the psilocybe azurescens. Contrarily, the strategies to grow the last 2 are very extraordinary to the system to develop Psilocybe cubensis. Buy psychedelic mushrooms or mushroom spores from your favourite dispensray, Buy Magic Shrooms Online UK.

Magic Mushroom Grow Kit

Developing or growing your own magic mushrooms is somewhat more troublesome than developing your very own cannabis. Firstly, before you begin with the culture of the organism, one must know about specific standards and work in all aspects accurately. Moreover, it is well known that the parasite societies are at risk for microscopic organism. It is also recommended to work on sterile glass and continuously observe so it doesn’t turn out bad. Hence, getting a well-organized and defined magic mushroom grow kit is the key solution here. Buy magic mushroom grow kit from us now to start your little farm and watch it grows large.

Psilocybe cubensis is a species of psychedelic mushroom whose principal active compounds are psilocybin and psilocin. Commonly called shrooms, magic mushrooms, golden halos, cubes, or gold caps, it belongs to the fungus family Hymenogastraceae and was previously known as Stropharia cubensis.

Where does the name Psilocybe come from?

The genus name Psilocybe is a compound of the Greek elements ψιλός (psilós) “bare” / “naked” and κύβη (kúbe) “head” / “swelling”, giving the meaning “bare-headed” (i.e. bald) referring to the mushroom’s detachable pellicle (loose skin over the cap), which can resemble a bald pate.-

Class: Agaricomycetes

This class is very diverse with over 16,000 species. Typically these organisms have mushrooms (fruiting bodies) used for reproduction. A lot of edible mushrooms fall within this class but Chlorophyllum molybdites is not one of those.

3 Potential Health Benefits of Microdosing Psychedelics

Proponents say that taking nonhallucinogenic doses of a psychedelic may deliver psychological perks, but much more research is needed, and we simply can’t draw conclusions yet.

Potential Health Benefits of Microdosing Psychedelics

Psychedelic therapy as a possible treatment for conditions like depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, eating disorders, and more seems potentially promising. And microdosing — in theory, a method of taking psychedelics in nonhallucinogenic doses — may deliver some psychological benefits. That said, it is vastly underresearched in the already complex field of psychedelic therapy and, in many cases of certain psychedelics, is illegal in the United States.

Here’s what we know about microdosing right now. (Hint: It’s not much.)

An Overview of Psychedelic Therapy

Here’s the main idea: Under the guidance of healthcare practitioners, often in clinical trials only, patients may take therapeutic doses of psychedelic substances, such as psilocybin (from “magic mushrooms”), LSD, MDMA, or ketamine, to experience a conscious-altering trip and potentially enact brain changes that affect the way they think, helping to pull them out of their psychological condition.

However, there are several downsides to psychedelic therapy, including legal complexities, potential side effects, adverse psychological challenges, and the extent of treatment, which requires lengthy and multiple sessions to possibly take effect.

In psychedelic therapy, some patients may not want to hallucinate — and that’s where a microdosing approach comes in.

It’s important to note that this article serves only as an informational resource about what we know on microdosing to date. Everyday Health is not in any way condoning the illegal use of psychedelic drugs for therapeutic or recreational purposes.

What Is Microdosing?

Microdosing psychedelics does not have an officially recognized medical definition or dosage amount, according to Harvard Health Publishing. But as the name suggests, microdosing is generally considered to mean taking less than the dosage needed to create hallucinogenic effects, per one research article. Though at this point, there are more questions than answers.

In one explanation from her own research, Harriet De Wit, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, describes microdosing as “taking very low doses of these drugs, about one-tenth of what you’d take to trip, and you take this dose every three to four days over an extended period of time.” For instance, you may need 100 micrograms (mcg) to get high; microdosing would be in the 10 to 20 mcg range.

According to most published research, microdosing is in reference to LSD, though there are also anecdotal reports of microdosing with psilocybin and MDMA, Dr. De Wit says. In theory, these low doses don’t cause hallucinogenic effects, but the goal behind microdosing is that taking small doses may change your brain under the radar, while you’re fully conscious and aware, and with the hope that this improves your sense of well-being overtime, she explains.

Challenges to Psychedelic Medicine

In regard to psychedelic therapy in general, and microdosing more specifically, it’s important to note two things.

Legalities Are Incredibly Complex and Evolving

Most psychedelics remain illegal for use, either in full doses or microdoses.

Esketamine (Spravato), a form of ketamine delivered via a nasal spray, was approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019 for treatment-resistant depression when used under supervision in a medical setting, and it is the only substance considered a psychedeliclike medicine that’s federally legal.

Psilocybin has been approved by certain states, such as Oregon, for supervised use, and though licensed facilities administering the drug have not yet opened, some plan to do so in the coming months, according to an April 2023 article from Oregon Public Broadcasting.

LSD is considered a Schedule 1 drug, which is defined by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration as having “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Still, legislative efforts to decriminalize psychedelics (on local and state levels) are growing, according to research.

That could all change, as the FDA released draft guidance in June 2023 for clinical researchers conducting studies around the use of psychedelic drugs as a potential treatment for psychiatric or substance use disorders. One obvious pain point is the need for more standardized clinical studies on these substances, and the FDA’s guidance advises on study design through drug development of psychedelic medicines. (This is currently in draft form, and the public has a chance to comment before the final version is released.)

Research Isn’t Clear (or Established)

What’s more — and this is key to keep in mind — research on psychedelic medicine is still in early stages, and the results are mixed. Studies are currently performed in academic medical settings via clinical trials, with the premise that participants take hallucinogenic doses of these substances, and research has a long way to go to draw more clear and widely applicable conclusions.

There’s even less data on microdosing, and many of the purported health benefits are only assumed from larger-dose trials. Even the benefits listed below may end up not being actual benefits of microdosing, as research evolves and becomes more clear in the coming months and years. Fundamentally, more research is needed, and it’s crucial to take the excitement surrounding psychedelic therapy with a grain of salt until we know more.

With all of that in mind, here’s what some experts and research presume about the possible health benefits of microdosing — though again, this could change.

1. May Lead to a Short-Term Mood Boost

LSD acts on the same serotonin neurotransmitter system as SSRIs, which are common antidepressant medications. That’s why there are theoretical reasons why the scientific community suspects that LSD taken as a hallucinogenic dose or microdose may be beneficial in mood disorders, De Wit explains.

De Wit and other researchers looked at this in a study in which people who did not have depression were given either a placebo, 13 mcg of LSD, or 26 mcg of LSD every three to four days, then monitored on their mood, cognitive performance, and responses to emotional tasks. (Both LSD doses were considered microdoses, for the study’s purpose.) The 26 mcg dose produced “feeling a drug” and stimulant effects when the drug was taken, but it did not change mood or cognition over the four-week course of the study.

That was admittedly a little disappointing to the researchers. “We were hoping to see a decrease in depression or anxiety scores, or more feelings of well-being. But the benefits were mixed and minimal,” says De Wit. “Each direct dose produces some feelings of well-being and energy, but over time that declines a bit, and you feel those effects less and less with each dose.” In the end, De Wit and her research colleagues could not find real improvements in feelings of well-being or behavior different from a placebo.

The placebo effect in medicine is well known and real, but there are downsides to banking on a placebo effect for benefits. That can lead to exploitation, says De Wit. “You want to make sure that claims made about a drug are genuine,” she says.

Another study randomized healthy male adults to take LSD or a placebo. The LSD group took 14 doses of 10 mcg of LSD every three days over six weeks. Ten percent of the LSD group dropped out due to treatment-related anxiety. Over the course of the study, daily questionnaires showed that people felt more creative, connected, energetic, and happy, as well as less irritable, and they experienced greater well-being on the days they were given the drug. However, these benefits were short-lived.

2. May Enhance Mental Performance and Creativity

One of the anecdotal benefits of microdosing is that it enhances creativity.

In research on microdosing psychedelic truffles (mushrooms), people who took a small dose of these psychedelics tested better on creative problem-solving tasks and cognitive flexibility compared with those who didn’t take these drugs. This study did not have a control group, and it was not measured against a placebo. Researchers point out that psychedelics may activate certain brain receptors linked to learning and adaptivity, which may increase the personality trait of openness and decrease rigidity in thinking.

In addition, a survey that recruited microdosers from online forums to complete questionnaires found that current and former microdosers rated higher on creativity, open-mindedness, and wisdom (the ability to learn from your mistakes while considering multiple perspectives), and lower on dysfunctional attitudes and negative emotionality, compared with nonmicrodosers. Most commonly, people used LSD and psilocybin. The researchers point out that people who have more dysfunctional attitudes tend to be more vulnerable to stress and depression. The sample used included mostly white, heterosexual, middle-class men, so a more diverse sample group is needed, as well as a more randomized and controlled population. Additionally, more controlled clinical trials would be needed to support claims of enhanced mental and creative performance

3. Low Doses May Still Allow You to Function Normally

Microdosing is more along the lines of taking a typical pharmaceutical drug, says Nese Devenot, PhD, a postdoctoral associate at the Institute for Research in Sensing at the University of Cincinnati. “While treatment with large doses requires 6 to 10 hours of your day and results in [potentially] profound alterations in one’s perception, a microdose can be iterated into your life because it’s a subhallucinogenic dose,” they say.

Some users say that microdoses produce no subjective effects, though many report that they do feel some stimulation. But in general, most people feel that they can go about their day as normal when microdosing, Dr. Devenot says, of their anecdotal understanding. Private advocacy groups, such as Moms on Mushrooms, aim to destigmatize microdosing plant-based medicines to take the edge off of the stress of parenting.

That said, one of the most common issues surrounding microdosing is accidentally taking too high of a dose. “If you’re trying to go to work, and objects and shapes are warping around you, that can be distracting and distressing if you were not prepared for an intense experience,” says Devenot. Plus, there are inherent risks if you’re driving, operating machinery, parenting, and doing other activities that require alert attentiveness.

Overall, the research cited here has found that microdosing (as it pertains to LSD) is generally safe for most people. However, there are many ways microdosing can go wrong. Unless you’re part of a clinical trial, you will most likely have to obtain the drugs illegally, which is not recommended by most doctors, scientific researchers, psychedelic experts, and certainly, Everyday Health. There are questions about the purity of the drug (if there are other substances within it) and variability of the dose, and that lack of control can be dangerous when you don’t know what you’re truly taking or how much, says De Wit. In addition, because there isn’t long-term research on microdosing, it’s not yet known if taking small amounts of one of these drugs changes the brain in unknown ways.

Bottom Line: We Need More Scientific Research

There are so many unknowns about microdosing. “People are considering these types of substances for all kinds of psychological disorders. It’s [uncharted] territory right now, since we don’t know what it does or who benefits,” says De Wit.

For Devenot’s part, they note that microdosing trials “have not stood up to the test of evidence-based science. I’m open to the science showing there are some benefits, but I’m not convinced from what I’ve seen that it’s more than placebo.” People who are desperate for answers, who want help with depression or PTSD or after a cancer diagnosis, commonly turn to the hope and promise of psychedelic medicine, but the science for microdosing is not there yet, she says.

That doesn’t mean microdosing should be entirely off the table as a possible route for healing in the future, however. “Though there is not enough evidence, an absence of evidence does not mean that it’s not working,” says De Wit. “It might mean that, as researchers, we haven’t found the right outcome to measure or that different people [and diagnoses] experience different benefits. But we haven’t seen them yet.” Still, this is an avenue that’s worth studying, within the greater context of psychedelic therapy, especially if people are experimenting on their own without telling their doctor. “This is a new era of psychedelic research that we should investigate in whatever way we can,” says De Wit

Psychedelic microdosing benefits and challenges: an empirical codebook

Background

Microdosing psychedelics is the practice of consuming very low, sub-hallucinogenic doses of a psychedelic substance, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or psilocybin-containing mushrooms. According to media reports, microdosing has grown in popularity, yet the scientific literature contains minimal research on this practice. There has been limited reporting on adverse events associated with microdosing, and the experiences of microdosers in community samples have not been categorized.

Methods

In the present study, we develop a codebook of microdosing benefits and challenges (MDBC) based on the qualitative reports of a real-world sample of 278 microdosers.

Results

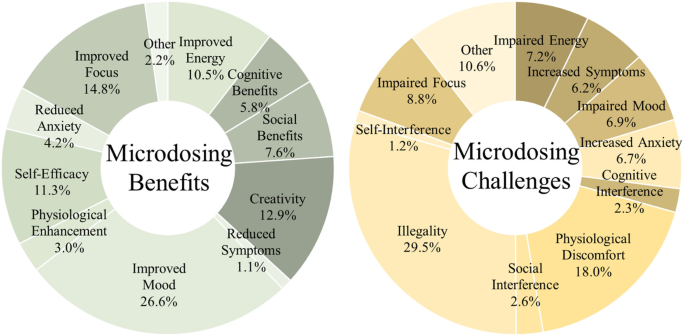

We describe novel findings, both in terms of beneficial outcomes, such as improved mood (26.6%) and focus (14.8%), and in terms of challenging outcomes, such as physiological discomfort (18.0%) and increased anxiety (6.7%). We also show parallels between benefits and drawbacks and discuss the implications of these results. We probe for substance-dependent differences, finding that psilocybin-only users report the benefits of microdosing were more important than other users report.

Conclusions

These mixed-methods results help summarize and frame the experiences reported by an active microdosing community as high-potential avenues for future scientific research. The MDBC taxonomy reported here informs future research, leveraging participant reports to distil the highest-potential intervention targets so research funding can be efficiently allocated. Microdosing research complements the full-dose literature as clinical treatments are developed and neuropharmacological mechanisms are sought. This framework aims to inform researchers and clinicians as experimental microdosing research begins in earnest in the years to come.

Introduction

The practice of microdosing psychedelics involves ingesting sub-hallucinogenic amounts of a psychedelic substance (e.g. LSD, psilocybin) and has recently grown in popularity. The number of popular media accounts and book-length treatments of microdosing has been growing [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Online microdosing communities have grown to the tens of thousands with more than 40,000 users subscribing to the /r/microdosing subreddit (/r/microdosing subreddit, Reddit Inc, San Francisco, CA, USA). This public interest speaks to a social need for scientific studies to inform the public about the effects of microdosing. Initial scientific investigations of microdosing are just beginning [8,9,10,11] (Rosenbaum D, Weissman C, Hapke E, Hui K, Petranker R, Dinh-Williams L-A, et al.: Microdosing psychedelic substances: demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and comorbid substance use, in preparation) and future directions remain unclear. While full-dose psychedelic research is growing in prominence and outcomes from full-dose studies can certainly inform microdosing studies, focusing solely on known full-dose outcomes could result in missing unanticipated benefits and challenges specific to microdosing. As such, beginning with an open, exploratory approach could result in a better understanding of the potential benefits and challenges specific to microdosing. The present study aims to provide a data-driven taxonomy describing the positive and negative experiences reported by microdosers from an open-ended analysis of microdosing-specific outcomes, summarizing high-potential avenues for focused experimental investigations.

The benefits of full-dose psychedelics

While more than a thousand early studies linked psychedelic use with beneficial effects [12], there was a 40-year pause on psychedelic research following the prohibition of these substances [13]. Despite continued prohibition, modern research has revealed the promising potential of LSD and psilocybin for treating alcohol and tobacco dependence [14,15,16,17], depression [18, 19], and end-of-life anxiety [20,21,22], while related research on 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) has shown great promise for treating post-traumatic stress disorder [23]. Psychedelics can also increase openness and occasion mystical-type experiences in healthy controls [24,25,26]. As full-dose psychedelics appear to aide in the relief of severe, chronic psychiatric conditions (e.g. depression, anxiety, PTSD), milder mental health concerns may plausibly be treated by lower, recurring doses. This is especially worth considering if certain full-dose outcomes are found to rely on purely pharmacologic mechanisms rather than primarily on phenomenological experiences [27].

Limiting microdosing research to topics that have been investigated in full-dose research could prematurely overlook unpredicted and potentially distinct microdosing outcomes. Full-dose research has employed various focal assessments of symptomatology, mood, and personality that are likely applicable to microdosing research, but due to the low doses and lack of perceptual alteration intended in microdosing, other full-dose phenomena, such as ego dissolution and mystical-type experiences, are less relevant to microdosing research. Instead, as a means of preparing for a broad range of outcomes, the present work solicited open-ended reports of benefits and challenges. Additionally, as psychedelic substances act on distinct yet overlapping neural receptor sites, it seems plausible that distinct patterns could emerge for different substances. The present study thus included microdosers who used LSD, psilocybin, or both.

The challenges of full-dose psychedelics

While psychedelics appear to have considerable potential benefits and low physiological risks [28,29,30], full-dose experiences can put participants under considerable psychological risk [31]. In a survey targeting participants that had at least one challenging experience (“bad trip”) with psilocybin mushrooms, 39% of respondents rated their full-dose experiences as among the top 5 most psychologically difficult/challenging experiences of their lives [32]. Griffiths et al. [20] used both “high” (22 mg/70 kg) and “low” (1 or 3 mg/70 kg) doses of psilocybin as experimental and control conditions, respectively. A dose-response effect could be seen such that in the high-dose condition, 32% of participants reported physiological discomfort whereas only 12% reported the same in the low-dose condition; likewise, 26% reported anxiety in the high-dose condition versus 15% in the low-dose condition [20]. Delayed-onset headaches are another possible side-effect of full-dose psilocybin [33].

To mitigate these risks, Johnson et al. [31] proposed safety guidelines for use with full-dose psychedelic substances, which rely on managing participant inclusion and having a comfortable, guided clinical setting. As microdosing does not involve the intensity of experience present in full-dose research, challenging experiences may be less likely. One may, however, anticipate that less frequent, less intense versions of full-dose challenges could be present even at the very low doses used in microdosing (e.g. restlessness instead of insomnia, mild anxiety instead of fear, mild headaches). As the study of microdosing is in its infancy, we could also expect there to be challenges that fall beyond the scope of reports based on full doses; the present study thus preferred open-ended surveying of drawbacks over pre-existing focal questionnaires.

Methods

The present study

In this study, we explored the benefits and challenges experienced by microdosers in a cross-sectional, retrospective, anonymous online survey. Respondents reported their subjective microdosing benefits and challenges (MDBCs) and the subjective importance of each outcome. We then used a grounded theory approach [34] to identify commonly-reported MDBCs and thereby deliver an empirical MDBC taxonomy to support future microdosing research. We also explored whether microdosing substances (LSD-only versus psilocybin-only versus LSD and psilocybin) were associated with different outcomes.

This study was part of a larger project that reported on the demographic and psychiatric comorbidities of the sample (Rosenbaum D, Weissman C, Hapke E, Hui K, Petranker R, Dinh-Williams L-A, et al.: Microdosing psychedelic substances: demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and comorbid substance use, in preparation) as well as a paper that addressed pre-registered hypotheses concerning mental health, personality, and creativity variables [8].

Grounded theory method

Microdosers were prompted to provide up to three benefits and up to three challenges associated with microdosing in small on-screen text boxes, resulting in short phrases (e.g. “Amplified emotions and better understanding of them”, “Fear of unknown effects, since its [sic] not studied”) or in one- or two-word responses (e.g. “Creativity”, “Better mood”, “Illegal”, “Too Energetic”). The coding authors (TA and AC) independently coded these benefits and challenges using the principles of classic grounded theory [34,35,36]. Discrepant codes were periodically discussed until a final set of codes was agreed upon (i.e. saturation was reached). These codes were hierarchically built into three layers of abstraction: codes (level one) were grouped under sub-categories (level two), which were grouped under categories (level three). This hierarchy was iteratively discussed and changes were agreed upon over five refining passes. We incorporated the diction used by the respondents where possible to better reflect the data-driven nature of the final codebook (see Additional file 1 and full online codebook; [37]).

Inter-rater agreement was calculated separately for benefits and challenges and at each level (code, sub-category, category). Agreement was above 85% at every level (benefit code 85.1%, benefit sub-category 89.2%, benefit category 92.6%; challenge code 85.7%, challenge sub-category 86.9%, challenge category 88.5%). Each report was coded twice, once by each coding author, and the sum of coded items in each category was halved; as a result, the frequency of any given category can be a non-integer value (e.g. 807.5 coded benefits, 603.5 coded challenges; “Empirical codebook: benefits of microdosing” and “Empirical codebook: challenges of microdosing” sections).

Respondents

Participation was voluntary under informed consent, in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was non-remunerative. The sample analysed in the present study includes the 278 respondents that answered the MDBC questions after indicating they had experience with microdosing LSD-only, psilocybin-only, or both LSD and psilocybin; respondents that indicated they used other substances to microdose (e.g. DMT, Salvia divinorum) are not included in the present report, allowing us to focus our efforts on the most commonly reported microdosing substances that are most likely to be studied in future research. Recruitment was primarily via the online forum “Reddit” (Reddit Inc, San Francisco, CA, USA). Reddit is an online forum with self-organizing sub-groups, called “subreddits”, which curate content for their “subscribers”. These subreddits discuss topics of mutual interest, making these communities potential pools of willing participants akin to other crowdsourcing approaches, e.g. Amazon mTurk, CrowdFlower, Prolific [38]. Compared to the US population, Reddit users tend to be younger, educated or seeking a college education, and present in a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1 [39] thus this sample’s generalizability is limited to modern Western populations. In the present sample, respondents had a mean age of 27.8 (SD 8.9); age was non-normally distributed with an interquartile range of 21–31 years (median 26.0, range 16–63). Most participants were male (M 237, F 31, other 10), heterosexual (N = 211, other 57), and white or European (N = 234, other 44). For a more comprehensive breakdown of all survey respondents, see our epidemiological report, which includes reports on psychiatric disorders (Rosenbaum D, Weissman C, Hapke E, Hui K, Petranker R, Dinh-Williams L-A, et al.: Microdosing psychedelic substances: demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and comorbid substance use, in preparation). Microdosers from the following subreddits were solicited: Microdosing, Nootropics, Psychonaut, RationalPsychonaut, Tryptonaut, Drugs, LSD, shrooms, DMT, researchchemicals, and SampleSize [40].

Design and questionnaires

Respondents completed a survey about their microdosing history including microdosing regimen (substance, dose, etc.), subjective benefits and challenges of microdosing, the importance of these benefits and challenges, and focal questions concerning behaviour and consumption changes. For concision, the numerous variables collected but not discussed here are not described here; many are discussed in our previous work [8] (Rosenbaum D, Weissman C, Hapke E, Hui K, Petranker R, Dinh-Williams L-A, et al.: Microdosing psychedelic substances: demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and comorbid substance use, in preparation) and the complete survey is available online [41]. Here we focus on questions concerning microdosing benefits and challenges (MDBCs), health behaviours, and substance-use changes.

Microdosing benefits and challenges (MDBCs)

Microdosing respondents reported up to three benefits and three drawbacks of microdosing psychedelics. They also gave each outcome a rating of subjective importance on a sliding scale from 0 to 100 [42].

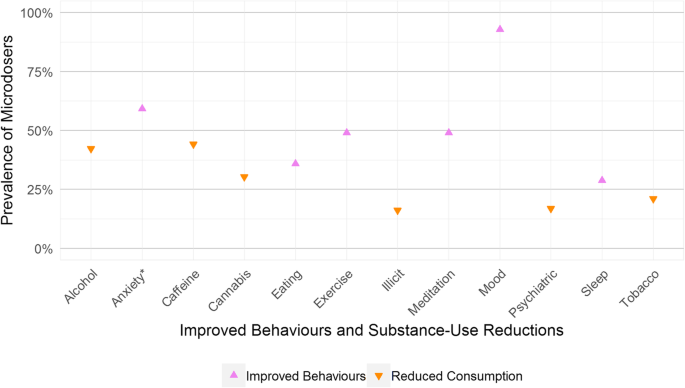

Improved health behaviours and reduced consumption

Microdosing respondents indicated whether they had, as a result of microdosing, experienced improvements in each of the following domains: mood, anxiety, meditative practice, exercise, eating habits, and sleep. They also indicated whether they had reduced their use of any of the following substances: caffeine, alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, psychiatric prescription medications, and illicit substances. These questions appeared on the page after the open-ended benefits and challenges questions to avoid contamination via priming.

Results

Microdosing substances

Respondents reported the substance they used to microdose and were removed if they indicated using substances other than LSD or psilocybin. This sample includes 278 respondents in three categories: LSD-only (N = 195), psilocybin-only (N = 50), and respondents that have microdosed with LSD and psilocybin (N = 33).

Empirical codebook: benefits of microdosing

Grounded theory analyses resulted in a total of 807.5 coded benefits of microdosing. Taxonomy-building resulted in 46 codes organized into 21 sub-categories and 11 categories. The most frequently reported codes were improved mood (12.8%), improved focus (10.0%), creativity (9.4%), and improved energy (7.6%).

Categories of benefit

This summary provides descriptions of the 11 categories of benefits that were distiled from participant reports (Fig. 1). As per grounded theory, the naming conventions for codes reflect the language used by respondents, but more flexibility was introduced as needed at higher orders of abstraction. Full descriptions of every code are available in the full codebook (see Additional file 1).

Categories of microdosing benefits and challenges. Values indicate percentage endorsement of outcomes. Values were generated through open-ended responses, and thus magnitude is descriptive and should be used for hypothesis generation. These data indicate reported outcomes, not confirmed effects

Improved mood (26.6%, 215 reports): This most frequently reported benefit-category captures all codes related to mood improvements: happiness, well-being, peace, calm, and reductions in depressive symptoms. Also included are reports of improved outlook, appreciation of life, optimism, spiritual and emotional insights, and being more in touch with emotions.

Improved focus (14.8%, 119.5 reports): This benefit-category references codes concerning focus and concentration, conscious awareness, mindfulness, and increased engagement and attentiveness.

Creativity (12.9%, 104 reports): This category includes creativity per se, as well as meta-creative processes, e.g. shifting perspectives, divergent thinking, curiosity, and openness.

Self-efficacy (11.3%, 91.5 reports): This category references improvements in self-efficacy (motivation/ambition, productivity, confidence, sense of agency) and self-care (introspection, meditation, and other behaviours facilitating mental health).

Improved energy (10.5%, 84.5 reports): This category includes codes referencing “improved energy” per se, as well as alertness, wakefulness, and stimulation.

Social benefits (7.6%, 61 reports): This category references various socially facilitating benefits such as extraversion, empathy, sense of connection, and verbal fluency.

Cognitive benefits (5.8%, 47 reports): This category concerns cognitive enhancement (understanding, problem-solving), clarity of thought (clear headedness, lucidity), and memory.

Reduced anxiety (4.2%, 34 reports): References to anxiety reduction and social-anxiety reduction fit in this category.

Physiological enhancement (3.0%, 24 reports): This category concerns biological processes including enhanced senses (especially visual), cardiovascular endurance, sleep quality, and reduced migraines and/or headaches.

Other perceived benefits (2.2%, 18 reports): This category was a catch-all for otherwise uncategorized codes. These include the novelty of the experience itself, the ability to control the dose, the lack of side-effects, and other miscellany. This category also includes 1 report that there were no beneficial effects.

Reduced symptoms (other) (1.1%, 9 reports): References to stress reduction, reduced sensitivity to trauma, and references to reduced substance dependence (e.g. quitting smoking) are included.

Empirical codebook: challenges of microdosing

Grounded theory coding resulted in a total of 603.5 coded challenges of microdosing. Taxonomy-building resulted in 44 codes organized into 23 sub-categories and 11 categories. The most frequently reported low-level codes were illegality (10.8%), dose accuracy (9.1%), poor focus (8.8%), and anxiety (5.3%).

Categories of challenges

As above, this summary provides extended descriptions of the 11 categories of challenge (Fig. 1).

Illegality (29.5%, 178 reports): This category captures codes concerning the illegality of psychedelic microdosing substances per se, as well as codes concerning the consequences thereof. These include dosing challenges associated with unregulated substances (e.g. taking too much or too little), the availability of the substance (i.e. dealing with the black market), and cost of the substance. Also included is the social stigma surrounding the use of these substances and feeling the need to hide one’s activity from others.

Physiological discomfort (18.0%, 108.5 reports): This category concerns physically detrimental challenges including disrupted senses (visual), temperature dysregulation, numbing/tingling, insomnia, gastrointestinal distress, reduced appetite, and increased migraines and/or headaches.

Impaired focus (8.8%, 53 reports): This challenge category references codes concerning poor focus, distractibility, and absent-mindedness.

Increased anxiety (6.7%, 40.5 reports): References to increased anxiety (general, social, existential) fit in this category.

Impaired energy (7.2%, 43.5 reports): This category includes codes referencing both excessive energy (restlessness, jitters) and inadequate energy (fatigue, drowsiness, brain fog).

Impaired mood (6.9%, 41.5 reports): This category includes codes related to mood deterioration (sadness, discontent, irritability), emotional difficulties (over-emotionality, mood swings), and impaired outlook (fear, feeling unusual).

Social interference (2.6%, 15.5 reports): This category references various socially impairing challenges such as awkwardness, oversharing, and difficulties with sentence-production in social settings.

Cognitive interference (2.3%, 14 reports): This category concerns confusion, disorientation, racing thoughts, and poor memory.

Self-interference (1.2%, 7.5 reports): This category references codes concerning self-processing concerns (dissociation, depersonalization) and self-sabotaging (rumination, over-analysis).

Other perceived challenges (10.6%, 64 reports): This category was a catch-all for otherwise uncategorized codes. These include the unknown risk-effect profile of microdosing itself, the need to prepare and remember to dose, references specifically citing that there were no challenges (1.5%), and other miscellany. This category also includes reports that there were no beneficial effects (0.6%). Furthermore, this category includes substance-related concerns regarding taste, pupil dilation, and duration of effects, and also concerns about negative drug interactions.

Increased symptoms (other) (6.2%, 37.5 reports): References to after effects (psychological dependence and concerns about potential addiction, substance tolerance, comedown or hangover) and also more concerning, but rare, adverse psychological events (0.7%).

Benefits and challenges by microdosing substance

Subjective importance ratings were non-normally distributed thus Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare between substances. There was a significant difference between the subjective rated importance of benefits based on substance (W = 3658, p < 0.01, N1 = 195, N2 = 50, d = 0.353) with psilocybin-only microdosers (median = 87.83, SD = 15.76) rating benefits as significantly more important than LSD-only microdosers (median = 76.67, SD = 14.59); there were no differences found relative to respondents using both LSD and psilocybin (median = 82.33, SD = 14.28, ps > 0.14). The substance-related difference between subjective importance of challenges was non-significant (W = 3841.5, p = 0.56, N1 = 177, N2 = 46, d = 0.079) with psilocybin-only microdosers (median = 47.67, SD = 24.98) rating challenges equivalently to LSD-only microdosers (median = 47.5, SD = 24.65); there were no differences found relative to respondents using both LSD and psilocybin (median = 51.67, SD = 23.79, ps > 0.66). Rates at which specific MDBC categories were reported did not differ between LSD-only, psilocybin-only, and LSD and psilocybin respondents (benefits χ2(20) = 17.26, p = 0.636; challenges χ2(20) = 7.73, p = 0.994).

Improvements and reductions

After reporting open-ended outcomes, participants answered targeted questions concerning behavioural improvements and substance-use reductions (Fig. 2). Respondents reported improved mood (92.9%), anxiety (59.2%), meditative practice (49.1%), exercise (49.1%), eating habits (36.0%), and sleep (28.8%). They also indicated reduced use of caffeine (44.2%), alcohol (42.3%), cannabis (30.3%), tobacco (21.0%), psychiatric prescription medications (16.9%), and illicit substances (16.1%).

Percentage of microdosers endorsing improved behaviours and reductions in substance-use. Prevalence rate should be used for hypothesis generation as these data indicate reported outcomes, not confirmed effects. *Note: Anxiety refers to improvements to anxiety-related experiences, not to increased experience of anxiety

Discussion

Surveying extant communities of microdosers allowed for the creation of an initial qualitative taxonomy of MDBCs. These empirically-grounded MDBCs can inform future microdosing research by leveraging participant reports for high-potential intervention targets so research time and funding can be efficiently allocated. For example, microdosers often report changes in mood, focus, and creativity thus these constructs should be targeted in future intervention research. Concerns of physiological discomfort and restlessness were also commonly reported thus they should also be monitored.

While the improvements and reductions reported by respondents sound promising, they cannot be disentangled from expectation and placebo effects or recall biasses. Furthermore, the MDBC findings cannot indicate causation as this study was observational, not experimental. With these caveats in mind, we discuss how researchers can use these initial findings in their future studies. While necessarily inconclusive due to their exploratory nature, these results point to potential therapeutic effects warranting future placebo-controlled microdosing research.

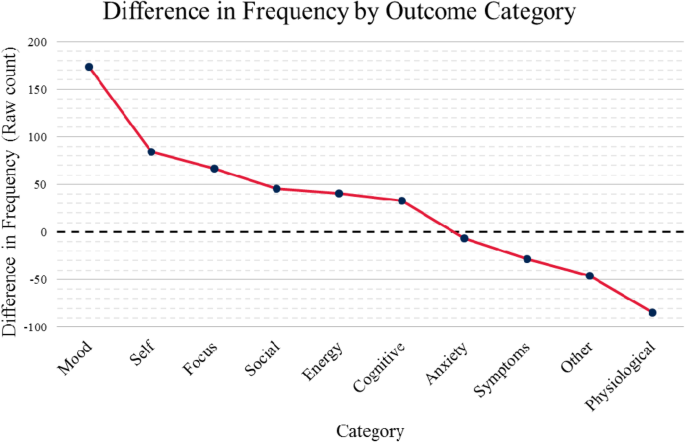

Emergent parallelism

Major parallels between benefits and challenges emerged among outcomes. Specifically, each category of outcome is seen as both a benefit and a challenge, other than creativity and illegality (Table 1). This kind of mirroring suggests two hypotheses concerning microdosing: (1) placebo effects and expectancy play a major role in reported effects and/or (2) individual differences moderate reported effects.

The first and most parsimonious hypothesis that could explain the parallelism between benefits and challenges is that the effects cancel out and nothing replicable is happening. The presence of opposite outcomes with a net-zero effect is what might be expected in an inactive condition dominated by noise. For example, if microdosing has no effect, random variation might result in some participants reporting decreased anxiety while others report increased anxiety. It may also be the case that microdosing interacts with expectancy in some way, enhancing the effect of expectancy and thus the outcomes could differ even more than anticipated based on the mind-set of the microdoser. Indeed, “set and setting” are major components of full-dose psychedelic use and expectancy is understood to greatly alter the outcome potentials of full-dose psychedelics [31]. Perhaps “set and setting” are also of importance in microdosing, though this remains to be tested. Indeed, each of the constructs described in this taxonomy should be directly tested in placebo-controlled trials.

Nevertheless, there are plausible pharmacological mechanisms of action for microdosing, and it is possible that individual differences in genetically mediated substance metabolism, psychopathological diagnoses and personality, and momentary interpretations of interoceptive signals affect how microdosing outcomes manifest. The HTR2A gene, which encodes the serotonin 5HT-2A receptor, can have various mutations [43] which, alongside other genetic and epigenetic influences, play a role in how 5HT-2A agonists, including LSD and psilocybin, are processed neuropharmacologically. As such, individual differences in receptor sensitivity may moderate optimal microdosing doses, substance choice, and dosing schedule. Genetic and epigenetic factors also influence psychopathology and personality, which can moderate responses to psychedelics [44]. For example, a person with a mood disorder (e.g. major depression) may find that microdosing has a different effect than a person scoring in the healthy range on a depression inventory. One possibility is that increasing between-network functional connectivity could disrupt the patterned use of cortical networks overly favoured under a specific pathology (e.g. to disrupt the greater functional connectivity between the DMN and subgenual prefrontal cortex seen in depression; [45]). In contrast, altering the functional connectivity in a healthy brain could plausibly produce undesirable activity rather than maintain healthy network coherence [46, 47]. Indeed, even in non-pathological participants, top-down interpretations of interoceptive events could cast physiological experiences (e.g. arousal) in a negative light (e.g. restlessness) rather than a positive one (e.g. wakefulness). These different interpretations may be amenable to intervention by preparing participants for certain physiological outcomes [31] whereas the genetic, epigenetic, and psychopathological features could constitute more stable predictors. These moderation hypotheses remain for future research.

While parallelism emerged, not all categories were equally reported on both sides of the benefit/challenge divide (Fig. 3). When calculating the difference between how often categories of benefits were reported versus how often the parallel challenge-category was reported, the three largest differences in raw reporting rates were mood being more often improved (215 as benefit versus 41.5 as challenge), self-efficacy being more often increased (91.5 benefit, 7.5 challenge), and physiological response being more often discomforting (24 benefit, 108.5 challenge). These categories may provide especially promising starting points for future microdosing research. Anxiety was closest to even with the difference being only 6.5 reports (34 benefit, 40.5 challenge).

Difference in raw count of reported benefits and challenges. Positive values indicate greater endorsement of benefits in the indicated category; negative values reflect greater endorsement of challenges. Comparisons are exploratory thus differences, regardless of magnitude, should be used for hypothesis generation. These data indicate perceived outcomes and do not indicate confirmed effects

Unique outcomes

Parallelism between benefits and challenges was not universal. The taxonomy includes both unique beneficial and detrimental outcomes: (1) creativity and (2) illegality.

Creativity was the third most common benefit category, and there was no opposite challenge (i.e. participants did not report that microdosing made them less creative or more closed-minded). Microdosers report enhanced creativity and meta-creative processes, such as perspective-shifting/divergent thinking and openness/curiosity. These findings accord with other findings that microdosers have higher creativity than non-microdosers [8, 11] and with full-dose research showing increased openness after full-dose psilocybin [24]. Early psychedelic research preliminarily investigated creativity enhancement and problem-solving [48], and this exciting topic could again be subject to study. Future studies should initially measure various aspects of creativity—e.g. divergent thinking, convergent thinking, insight [8, 11, 49, 50]—to inform more focal investigations on how microdosing may affect creativity.

Illegality was the most commonly reported microdosing challenge. It is notable that the most frequently reported “outcome” is a socio-cultural circumstance, not an outcome of microdosing per se. Psychedelics were made illegal by the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 1971 and remain so today [13, 51]. Illegality has resulted in a thriving black market economy for illicit substances, both in-person and online [52]. This unregulated criminal market results in unpredictable substance purity, dose accuracy, supply availability, and cost. Illegality has further societal consequences, namely the social stigma associated with substance use, even though psychedelic substances have a relatively benign safety profile compared to other substances, including several legal substances [53]. As such, researchers have begun calling for the legal rescheduling of psychedelic substances [54].

Improvements and reductions

In addition to the emergent qualitative categories, participants reported on several a priori focal outcomes (Fig. 2). Nine-tenths of respondents endorsed that microdosing improved their mood, which is in agreement with improved mood being the most commonly reported benefit-category. Anxiety improvement was also notable with 59% of respondents indicating this benefit. These rates of reported improvement suggest future research into microdosing for mood and anxiety may be warranted, complementing the recent work treating depression and anxiety with psilocybin [19, 20].

Participants also indicated decreased use of caffeine, alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco (Fig. 2). These findings align with research on full-dose psychedelics: LSD and psilocybin may promote reduced alcohol abuse [14, 16], and psilocybin can have potent long-term reductions in smoking [55]. Microdosing could be investigated as a potential complement, supplement, or alternative to full-dose interventions for smoking cessation or substance use disorders.

Limitations and future directions

The intent of the present study was to inform empirically-grounded data-collection initiatives by providing high-potential outcomes deserving of further study, while also showcasing challenges that warrant measurement and suitable caution. The intent of the present study was not to make causal claims. We employed no experimental manipulation or longitudinal component, could not control for substance purity, schedule, or dose, nor for prior experience with full-dose psychedelics, and we cannot account for recall bias or placebo effects. MDBCs described here reflect the reports of microdosers, but we cannot claim that these perceived outcomes are causally related to microdosing. LSD and psilocybin were the most frequently used substances and, as microdosing continues to be culturally, scientifically, and clinically relevant, it will be important to establish dose-dependent outcomes of microdosing and to consider the different contexts in which micro- and full doses may be variably appropriate, including when they may complement each other.

Our participant recruitment strategy relied on self-selection and sampled primarily from Reddit; this strategy may have introduced demographic biasses, and these data should not be considered epidemiologically definitive (see Rosenbaum et al. (Rosenbaum D, Weissman C, Hapke E, Hui K, Petranker R, Dinh-Williams L-A, et al.: Microdosing psychedelic substances: demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and comorbid substance use, in preparation) for further discussion). More than 70% of the sample reported countries of Anglo-cultural origin, and this sample is limited in the sense that it does not reflect a random sampling of the human population. We sought a sample of psychedelic microdosers, a group that may not be randomly distributed in the population, thus this convenience sample is still informative. Nevertheless, future intervention work should endeavour to recruit more inclusive and representative samples.

Qualitative research is, by its nature, biassed by the research team and their coding decisions. MDBCs were processed by two interdependent coders (TA and AC) that iteratively constructed the agreed-upon codebook. Hypothesis-driven coding was avoided to maintain code-integrity [36] and, supporting transparency and re-analysis, both the coded and raw data have been made available [41]. Another taxonomy could emerge from different investigators pursuing more targeted research questions, so these MDBCs should not be taken as definitive. The present taxonomy offers a foundation from which future focal research can be built.

Ultimately, pre-registered randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) of microdosing psychedelics are needed to test its safety and efficacy. Using the MDBC taxonomy as a starting point, appropriate measures can be included to investigate the causal outcomes of microdosing and the mechanisms underlying those outcomes. The potential of microdosing is not yet well understood, but the benefits reported in this taxonomy suggest potential novel research avenues for psychedelic-based pharmacotherapeutic treatment of depression, anxiety, ADHD, smoking cessation, and substance use disorders. Exploring the potential of microdosing for creativity is also warranted.

Conclusion

Here we provide an initial taxonomy of benefits and challenges associated with psychedelic microdosing, which compliments the other reports built from this larger microdosing research project [8] (Rosenbaum D, Weissman C, Hapke E, Hui K, Petranker R, Dinh-Williams L-A, et al.: Microdosing psychedelic substances: demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and comorbid substance use, in preparation). The findings presented here suggest a number of potential microdosing research avenues, though experimental, hypothesis-driven studies are needed. The MDBC taxonomy, behavioural improvements, and substance-use reductions warrant RCTs to test therapeutic safety and efficacy of microdosing psychedelics. Online microdosing communities have grown to the tens of thousands, speaking to a social need for scientific study to inform the public about the effects of microdosing. Microdosing research could help inform future psychedelic research by investigating the potential for mixing or contrasting micro- and full-dose psychedelic psychotherapies. We call researchers to do this work following the principles of open science and share our resources accordingly [41]. After a 40-year moratorium, the psychedelic renaissance has begun: rigorous scientific methods can now be used to investigate psychedelics as potential medicines and for “the betterment of well people” [1].

FREE BENEFITS OF MICRODOSING SPORE WELLNESS MUSHROOM CAPSULES

Spore Wellness Microdosing Mushroom Capsules – The Micro Bundle (Cognitive, Energy, & Immune)

Spore Wellness The Micro Bundle gives you an opportunity to try all the blends in the Spore Wellness Microdosing Mushroom Capsule product line.

The Micro Bundle includes Spore Wellness Cognitive (SWC), Energy (SWE), and Immune (SWI). Each formulation is intended to help with your intended goals whether it’s achieving zen in your life, higher performance or simply feeling better.

Spore Wellness is our #1 top selling microdosing mushrooms brand.

Each bottle contains 25 capsules (500mg per capsule). Vegan and gluten free.

Benefits of Microdosing: Non-psychoactive, Improved mood, Increased creativity, Improved focus, Improved energy, Improved memory, and Self-efficacy.

Learn about each one of the Spore Wellness blends here:

Spore Wellness Cognitive – Recommend Use: Promotes mental clarity, focus and memory.

Spore Wellness Energy – Recommended Use: Promotes & supports daily energy levels.

Spore Wellness Immune – Recommend Use: Promotes & supports immune system health.

Spore Wellness The Micro Bundle gives you an opportunity to try all the blends in the Spore Wellness Microdosing Mushroom Capsule product line.

The Micro Bundle includes Spore Wellness Cognitive (SWC), Energy (SWE), and Immune (SWI). Each formulation is intended to help with your intended goals whether it’s achieving zen in your life, higher performance or simply feeling better.

https://trippyfantasy.com/product/spore-wellness-microdosing-mushroom-capsules-the-micro-bundle-cognitive-energy-immune/

Spore Wellness is our #1 top selling microdosing mushrooms brand.

This common Autumn mushroom has been illegal to pick, prepare, eat or sell since 2005 as they are now considered a class A drug. Liberty Caps contain the active ingredients psilocybin and psilocin, which can cause hallucinations and in some cases, nausea or vomiting.

| Mushroom Type | |

| Common Names | Liberty Cap (EN), Magic Mushroom (US), Shroom (US), Cap Hud (CY), Łysiczka Lancetowata (PL), Hegyes Badargomba (HU) |

| Scientific Name | Psilocybe semilanceata |

| Season Start | Sep |

| Season End | Dec |

| Average Mushroom height (CM) | 5 |

Average Cap width (CM) CapThe cap can vary in shape, size and colour. When young it is translucent brown and will stay brown if the weather is wet, if the cap dries it becomes buff/white/grey/silver but almost always has a darker to black bottom edge. The cap has a ‘nipple’ which can be quite pronounced or barely present and the bottom edge always tucks under. When fresh, the cap has a translucent covering that, if you are very careful, can be peeled away. GillsThe gills start light grey/black, are mottled and have a lighter edge but become very dark purple/black as the spores are released. StemThe stem is off white, slightly shaggy on close inspection, can have a blueish base with mycelium still joined. The stem usually curves and bends and is rarely straight. FleshHas very thin flesh. HabitatMore common in fields, moors and grassland where animals are grazed but can be found in lawns and in parks. Spore PrintDark purple. Ellipsoid. FrequencyCommon. Other FactsMagic Mushrooms are currently treated the same as heroin or LSD and are class A drugs but very recently (Oct 2021) the government was looking to change this due to the apparent benefits from treating certain illnesses with psilocybin and psilocin, the active components of Magic Mushrooms. These include chronic depression and PTSD. The research is ongoing but they do seem to be proving useful in the medical field |